Chán Theory & Practice

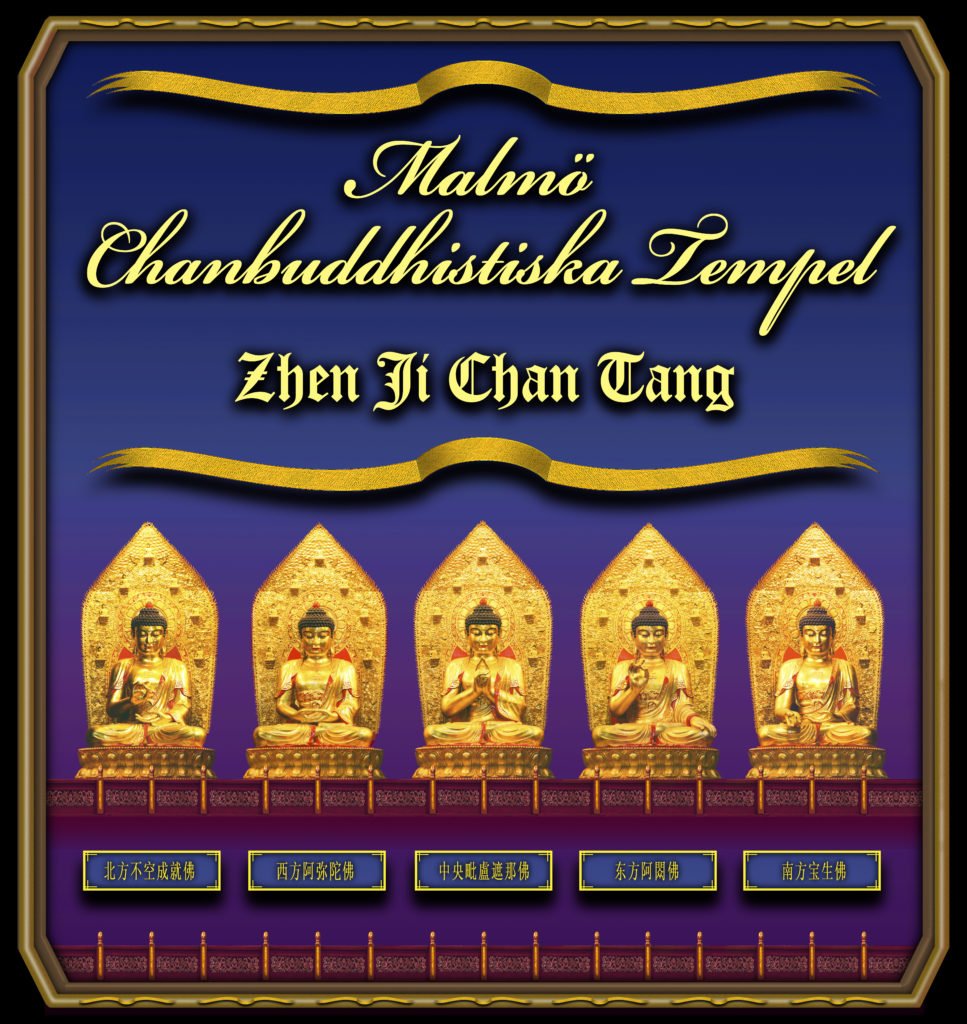

This lecture was delivered by the venerable master Jǐng Huì (净慧老和 – Jǐng Huì Lǎo-Hé ) on the 3rd day of the seventh lunar month of 2005, at the Zhēn Jì Chán Temple (真际禅林 ).

Today I would like to talk about the subject of Chán theory and practice. This subject can be separated into three distinct categories:

a) The Principle of Chán (禅理 - Chán Lǐ)

b) The Practice of Chán (禅行 – Chán Xìng)

c) The Style of Chán (禅风 – Chán Fēng)

The emphasis of this lecture is specifically upon the Chán method, and does not include the Six Paramitas (六度 - Lìu Dù).

1) About the Principle of Chán

Within the Buddhist tradition of “Chán” (禅), everyone is familiar with these four sentences, “Do not set-up words and sentences. Teach outside of tradition. Point directly to the mind. Perceive its true nature and attain Buddhahood.” The four sentences define the practice, purpose, essential spirit, and basic requirements of the Chán tradition. The four sentences convey the entire meaning of the Chán tradition. If we wish to study the Chán tradition, then a good student studies the four sentences. When the four sentences are understood, the great intention and purpose underlying the Chán tradition becomes apparent. In this way fundamental understanding is achieved, and the essential principle of Chán training becomes clear. From the point of view of the four sentences, what exactly is the “principle” of the Chán tradition? The four sentences explain that the principle of Chán cannot be satisfactorily explained in words. This is because Chán is defined in this manner, “Do not set-up words and sentences. Teach outside of tradition.” When this is understood no amount of words can be used to explain the Chán principle! The Chán principle is inconceivable and beyond the meaning of mere words. Even though the principle of Chán does not set up written texts and is not dependent upon words, it has to be understood that words as an expedient device, have been used to record and convey the teachings of the Buddha from one generation to the next. Without the use of words to preserve the teachings of the Buddha and the Patriarchs, then knowledge of the Chán Buddhist tradition would have been lost. However, it is also true that the use of words is not equal to the principle of Chán which utilizes silence whilst speaking, and speaking whilst silent. Therefore the principle of Chán remains beyond the reach of the use of words and may be considered speaking whilst remaining silent. To transcend the use of conventional words is to engage in speaking whilst remaining silent. This principle harmoniously embraces all things and establishes the order of the Buddha-Dharṃa world.

How should the Chán principle be defined? It is better that we rely upon the Patriarchs for guidance, rather than attempt to formulate a definition from our own, limited understanding. In this lecture I will only discuss the basic theory of Chán. The basic theory of Chán is contained within two source texts. The first text is from Patriarch Bodhidharma (达磨祖师 - Dá Mó Zǔ Shī) and is entitled “Two Entries; Four Methods” (二入四行 – Èr Rù Sì Háng), an article of a few hundred words, and the other text is from Sixth Patriarch Huì Néng (六祖大师- Liù Zǔ Dá Shī) and is entitled the “Three Non-concepts” (三无 – Sān Wú). From both these texts the framework of the basic theory of the Chán tradition is drawn. There are many other texts regarding the theory, method and practice of the Chán tradition, but none of these deviate from the meaning of the above two texts and maybe viewed as an elaboration upon the basic theory itself. The Patriarch Bodhidharma tells us, “There are many ways to enter the path, but in reality this does not go beyond two distinct methods; method one is entry through principle, whilst method two is entry through conduct.” Bodhidharma further explains this by saying that, “Entry through conduct (method two) is associated with four practices which must be observed”, but that “entry through principle” is the essence of the Chán path and explains the Chán tradition. In any method that practices the Dharṃa two aspects are equally developed; the first is insight development attained through meditation, whilst the other is the cultivation of physical discipline. The cultivation of insight is the essence of the principle, whilst diligent effort is the practice. The Buddha teaches that a practitioner must tread the middle path between the cultivation of insight and the application of physical discipline, so that the two distinct practices become unified. Oneness of practice is achieved through the cultivation of principle and the application of the four disciplines; this is the practice of Dharṃa. There are worldly paths that emphasis only “sitting” in meditation, but do not advocate physical discipline, this is not Buddhism. Authentic Buddhist practice is always the combination of the development of insight coupled with physical discipline.

The principle of the Chán tradition is compatible with the essential teachings of Buddhism, but the Chán tradition conveys the essence of Buddhist thinking in just a few words. The Patriarch Bodhidharma explains “entry through principle” with these few words, “Those who enter through principle understand that all beings – whether enlightened or unenlightened - share exactly the same true nature.” Of course, the term “unenlightened” refers to all ordinary beings without exception. The world is full of many ordinary beings whose outward appearance varies considerably, but in reality, each and everyone contains the same enlightened nature. The Buddha-nature of all beings is exactly the same. If this is the case, why not manifest this Buddha-nature here and now? Bodhidharma tells that: “The Buddha-nature is obscured by a layer of dust which prevents the ‘real’ from manifesting.” Everyone possesses Buddha-nature, but it cannot shine, it cannot function, due to this obscuring layer of dust which is actually comprised of delusion. This delusion covers and obscures our true nature and ensures an endless cycle of rebirth in the six realms of samsara. How can we regain our true essence and dispel the obscuring dust of klesa (烦恼 – Fán Nǎo)? The Patriarch Bodhidharma said: “Give up delusion and return to the real by concentrating (and stilling) the mind so that a broad and all-inclusive mind is achieved. Then there is no self or other and no difference between a sage and an ordinary person.” The Patriarch tells us that if we want to transcend delusion and return to our true nature, then we must “concentrate (and still) the mind so that a broad and all-inclusive mind is achieved.” What exactly is “concentrating (and stilling) the mind so that a broad and all-inclusive mind is achieved”? It is having a mind free from dualism, so that there is no distinction between a sage and an ordinary person. This being the case, then where does the delusion (klesa) in the mind originate? It originates because we think in dualistic terms and perceive an “I” and an “other” as being real. All delusion stems from a sense of self, the very reason that we cannot realize oneness of mind. When oneness is not present in the mind, then there is dualistic thinking without end. This means that we have an undeveloped mind. In this state it is difficult to understand that under the dualistic delusion the Buddha-nature is present. This is because ordinary people are not yet enlightened, unlike Bodhisattvas, Buddhas and Mahāsattvas, who have already attained enlightenment. Perhaps many of us think that enlightenment is a long time away as we will not have the opportunity to study the Dharma. Actually this is not the case. The delusion of dualistic thought can be broken immediately, here and now, and the apparent distinction between a sage and an ordinary person permanently transcended. If we practice with diligence and strive to over-come dualistic thinking, then the Buddha-nature will naturally manifest and all things will be contained within it. If we can achieve this unity, then when in society there will be no application of dualistic thinking, and no klesa will be generated that can cause suffering. This can happen in an instant, here and now, and is the entire purpose of the Chán tradition that does not set up distinctions. Chán is a great and powerful method for attaining enlightenment, and its strength shines through – here and now – in this very place.

Now, it may appear to take decades to achieve enlightenment for this person, or that person, but in reality, this is due to different life circumstances, which is the product of individual karma. The karmic burden may be heavy or light, either way the Buddha-nature is present here and now and it only has to be realized as such. Take those people surnamed “Wáng” (王) for example, why is it that some are university professors, whilst others are wealthy, and others still are unemployed, or without food or clothing? Why are there these differences? Of course the reasons for these differences can vary greatly, but from my own experience it seems that determination and striving is very important. These two attributes are often lacking in self-cultivation. Many take vows to the Buddha but lack the ability to follow those vows and therefore do not make any progress. Despite the initial aspiration the practitioner lacks the determination to succeed. This is like making empty promises. Those who do strive to follow their Dharmic vows with determination build good karma and eventually become virtuous sages. It is also the case that those who generally perform positive actions in their past lives, and who continue to act in a good manner in this present life, although they may not follow the Dharma, still continue to build a positive karma which leads to material riches. How we act now, in this very moment, is very important. This is why we must strive with effort here and now and engage in meditation with strength. We must develop mindfulness and disengage the mind from the emotions so that all attachments are transcended. We must be determined to transcend the boundaries of the personality that is defined by dualistic thinking, and cultivate an enlightened mind. If Bodhisattvas and Buddhas can achieve this, so why can’t we?

When we practice Buddhism today, we must be determined to follow the Buddha’s example, and the Buddha’s teachings. He has set the standard which we must follow correctly and without distortion. If we can do this, then we will enter the spiritual state and be as one with the Buddha. This means that the ordinary deluded mind is transformed, and the Buddha-nature – the true nature - is revealed as the Mind Ground in its all-embracing entirety. This instantaneous realization of the Mind Ground is the essence of the Chán principle, and is the sustaining strength of the Chán tradition. When the Mind Ground is realized, it is like coming back to life. The is the unsurpassed Dharma that the patriarchs have transmitted through the generations. Unfortunately, it is a shame that modern people lack the great strength of spirit required to follow this path. In the “Collected Sayings of Zhàozhōu” (赵州语录 – Zhàozhōu Yǔ Lú), we learn that when the monk Zhàozhōu mixed with many different people, he had a conversation with an old woman who was very wise and able to discuss the mystery with pin-point accuracy, as if she were wielding a sword of wisdom. In those ancient days, an old woman living in rural China was able to discuss the Chán method and demonstrate a considerable insight, even when face-to-face with an eminent monk such as Zhàozhōu. This is unusual and not always the case. Today, there are present many respectable lay women practitioners. However, many feel as if they possess very bad and heavy karma, and that their good karmic roots are shallow. They feel that their practice is difficult and that their progress is slow. They think that they cannot attain to Buddhahood, why is this? It is because they feel that bad karmic seeds have been planted a very long time ago, and that such a negative karma that has existed since the beginning of time is difficult to escape from. By looking within effectively, you can perceive the true nature in an instant. This is the essential spirit of liberation that lies at the center of the Patriarch’s Chán. It achieves complete liberation from suffering, from life and death, and from all dualist thinking. As a method it breaks down all barriers to the realization of enlightenment, and leaps over all duality into an equanimous “oneness” that is free, comfortable, natural, and a non-active (无为 – Wú Wéi) spiritual state. Everybody would like to achieve this state, and then they would be truly happy! You can achieve this in a single moment – why would you think otherwise? You can achieve this state of enlightenment here and now, and it will not cost a penny! All you have to do is have the courage and determination to commit yourself to following the Dharma, generating good karma and meditating with great strength. As the Patriarch Bodhidharma says about the theory of Chán, one aspect is “principle”, whilst the other aspect is “conduct”. Chán principle is looking within during meditation and contemplating the Mind Ground, emphasizing the development of insight. Following the discipline associated with the Dharma stresses the application of a great and diligent effort. Entry through conduct is defined through the four practices;

Entry Through Conduct

1) The practice of repaying wrongs.

2) The practice of adjusting to circumstance.

3) The practice of non-seeking or asking for anything.

4) The practice of upholding the Dharma.

These four practices have been discussed many times at the Bǎi Lín Temple (柏林寺 – Bǎi Lín Chán Sí) during Chán Week Retreats. However, today we are focusing upon the understanding of the Chán principle, and entry through insight. The Patriarch Bodhidharma explains the Chán principle (with regard to entry through insight) in the following manner:

Entry Through Insight

“When conveying the tradition of enlightenment, it is understood that all beings – whether enlightened or unenlightened - share exactly the same true nature. However, the Buddha-nature is obscured by a layer of dust which prevents the ‘real’ from manifesting. Give up delusion and return to the real by concentrating (and stilling) the mind so that it is broad, and all inclusive. Then there is no self or other, and there is no difference between a sage and an ordinary person. Firm and unmoving, there is no falling into the written teachings. This deep realization is in accord with the principle. There is no discrimination, and all is silent and non-active (无为 - Wú Wéi).”

This is the fundamental principle of Chán as taught by Bodhidharma. Bodhidharma laid the foundations of the Chán School in China. Despite the many changes that have occurred over hundreds of years, it can be said that Chán in China begins with this statement. This source is like a continuous trickle of water that eventually flows into a stream. This stream then flows into hundreds of rivers that combine to form the great sea of Chán. Although a mighty ocean today, it has a little trickle of water at its source.

The Sixth Patriarch’s text entitled the “Three No’s” (三无 – Sān Wú) I have also previously spoken about many times in the past. The “Three No’s” are “non-thought” (无念– Wú Nián), “non-form” (无相 - Wú Xiàng), and “non-abiding” (无住– Wú Zhù). This fundamental thinking is in accordance with the “Prajñā” (般若– Bōrě) principle of Buddhism, and the Mahāyāna teaching of “Dependent Origination and Empty Nature” (Yuán Qǐ Xìng Kōng - 缘起性空).

The Sixth Patriarch said, “Learned friends; it is the tradition of our school that “non-thought” is the teaching, “non-form” is the basis, and “non-abiding” is the foundation.”

How do we enter the Chán tradition, how do we enter the sublime state of thought of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas? First it is important to realize “non-thought”, that is non-thought whilst in the midst of thinking. Secondly it is necessary to realize “non-form”, that is non-form whilst in the midst of form. Finally the state of “non-abiding” must be achieved, but what does non-abiding mean?

“It is the essence of human nature. In all worldly actions, be they good or evil, pleasant or ugly, friendly or hostile, in times of dispute or quarrel, all this should be treated as empty, with no thoughts of retribution in the mind.”

This means that we have the deep and profound intention not to be attached to the good, or attached to the bad, but remain free of abiding in this duality. This is the permanent state of non-abiding which is achieved through non-attachment. The “Three Non-Attributes” are defined as; “No-thought as the teaching”, “non-form” as the basis, and “non-abiding” as the foundation. The ancestors teach that the “Three No’s” correlate with the basic “Three Teachings” (三学 – San Xue) of Buddhism in the following manner:

1) Śīla (discipline) = No-thought

2) Dhyāna (concentration) = No-form

3) Prajñā (wisdom) = no-abiding

Why is it said that ‘no-thought’ is the Śīla? This is because the discipline (Śīla) must be upheld in a manner that avoids the trap of duality. The discipline must be maintained whilst not maintaining it; and not maintained whilst maintaining it. When this is achieved in the mind, then everything unfolds naturally, and there is no need to intentionally seek after anything. In this way there is no interest in worldly fame; negative (intentions) and actions are avoided and good intention and actions are generated. In this state of being there is no fear associated with cause and effect, and virtuous actions are cultivated as a duty that becomes quite natural. The mind generates good (intentions) and actions without seeking anything, and in this way upholds the discipline.

No-form is associated with Dhyāna. Dhyāna is the central aspect of the Three Teachings of Buddhism, and maintains stability of action. Sometimes Śīla, Dhyāna and Prajñā are described using the metaphor of the human body. The feet represent Śīla; the torso represents Dhyāna, and Prajñā is represented by the head, eyes, and mouth. Therefore Dhyāna is the central aspect of our being. Cultivating Dhyāna correctly achieves the attainment of no-form. The cultivation of Dhyāna aims to free the practitioner from attachment to form; Dhyāna that remains attached to form is shallow and not deep as a practice. Only Dhyāna that is without form can be considered the great Dhyāna, (also referred to as the Śūraṅgama Samādhi). Achieving no-form Dhyāna is the essence of the Chán School.

No-abiding is directly associated with wisdom. When wisdom is successfully cultivated then the state of ‘no-abiding’ is manifest. If wisdom is not cultivated, then the practitioner remains trapped in the dualistic world of phenomena, and will remain influenced by the six senses (covered with dust), the five desires and will not be able to breakout of the deluded state of good and evil. No-form is the cultivation of the intent to eradicate all attachments (执著 – Zhí Zhāo) from the mind. Only when all attachment is eradicated from the mind will the inherent wisdom manifest. Therefore, no-thought, no-form, and no-abiding, equate with the Three Buddhist Teachings of Śīla (discipline), Dhyāna(concentration), and Prajñā (wisdom), and can be used specifically for Chán training. The “Three No’s” of the Sixth Patriarch lay a firm foundation for Chán training. The above lecture describes the fundamental principle of the Chán method. It can be summed-up as consisting of Bodhidharma’s “Two Entries” and the Sixth Patriarch’s teaching on the “Three No’s”. Both methods are of equal worth as they reveal the essence of the Mind and are in accordance with the saying: “In the state of non-duality, all things are equal.” If you can be like this, then you enter the state of Chán; if you cannot be like this, then the Chán state is completely missed.

2) About the Practice of Chán

What is the path of Chán? In fact, whilst describing the principle of Chán I have already spoken about the path of Chán. The principle and practice of Chán are inseparable, and I have spoken about how Chán practice is an integration of both principle and effort. When practicing Chán, it is the essence of the Buddha that is being studied, immediately, here and now. They are not two separate things, but one and the same entity. I only appear to speak of them as two separate subjects out of convenience to assist those who do not yet understand. What exactly is Chán practice? From Bodhidharma to the Sixth Patriarch the same Dharma of Unified Practice Samādhi (一行三昧 - Yī Xíng Sān Mèi) has been transmitted. What exactly is Unified Practice Samādhi? The Sixth Patriarch said, “Unified Practice Samādhi is the practice of Mind that remains consistently straightforward in all situations, whether walking, standing, sitting, or lying down.” He also said, “The mind that remains straightforward in all situations, whether walking, standing, sitting or lying down, is the Bodhimaṇḍala (道场 – Dào Chǎng), and is the true entry into the Pure Land. This is Unified Practice Samādhi.” What is the method for attaining this state whilst walking, standing, sitting or lying down? There are two attributes that must be achieved. The first is to establish a mind that is straight; the second is to realize that a straight mind is the Bodhimaṇḍala –or “spiritual center”. Therefore, when applying the practice of the four compassionate Bodhisattva Vows in relation to the three karma producing actions of deeds, words, and thoughts, the mind remains “straight” and does not stray from the Bodhimaṇḍala. This means that when the four Bodhisattva Vows are practiced continuously, then whether walking, standing, sitting, or lying down, all situations are the Bodhimaṇḍala. This is the subject of my small booklet entitled “There is nowhere in the green mountains that is not the Bodhimaṇḍala” (何处青山不道场 – Hé Chù Qǐng Shān Bù Dào Chǎng). Can we live in such a way so that walking, standing, sitting and lying down, is continuously in accordance with the spiritual center? Can lay life and life in a monastery be continuously in accordance with the spiritual center? Can we chant sutras, perform everyday tasks, meditate, and view a wife and child as being the Bodhimaṇḍala? I am afraid that many people cannot be like this. Many are unable to view lay life as being holy, but instead go to the temple to meditate. Where is their mind? In reality it is the mind that decides whether the spiritual center is continuously present, and which draws a distinction between worldly affairs and Buddhist practice in temples. In this deluded state the mind prefers the temple life and disdains the ordinary life. People are continuously worrying about what practice method they should use, or how much time per day should be spent practicing. You ask how to cultivate the practice? How much time in the day does it take to cultivate? As you seldom have much time to spare. What does the practice actually entail?

The Mind must be kept pure and straight. A pure Mind is a straight Mind, and a straight Mind is a pure Mind. Therefore a straight Mind is at one with the Bodhimaṇḍala, or spiritual center. Keep the Mind straight in every situation and do not bend to passing circumstances. There is not a single place that a straight Mind is not the Bodhimaṇḍala. Then every single circumstance becomes a function of the Buddha. If this is not the case, then you cannot escape from Saṃsāra. As there is no place from which you can escape, you will not be able to achieve the “Three Levels of Complete Enlightenment” (三觉圆满 – Sān Jué Yuán Mǎn), associated with the Arhat, Bodhisattva, and Buddha. This is because the barrier of delusion has not been eradicated from the mind. Eradicate this barrier – here and now – and clean the mind of it’s worries and confusions. In this way you can become a Buddha. This is to say that the mind must be swept clean, as if a hurricane of wisdom has broken up, scattered, and eradicated the dark clouds in the sky. When the clouds clear, the sky is filled with a great light – this is the attainment of enlightenment. Perhaps you think that if you have children your ability to follow the Buddha’s path is over. It seems realistic that having children prevents the Dharma from being practiced. You need to gain good experience. If you believe that Buddhism cannot be practiced in everyday life, then it will seem that the Dharma cannot be applied in ordinary situations. This is incorrect. It is important to expertly cultivate Unified Practice Samādhi when walking, standing, sitting and lying down, and then the Mind will be unified in purity. Then all situations become the Bodhimaṇḍala without exception, this is the true meaning and practice of Unified Practice Samadhi.

What does it mean to study Samādhi (三昧 – Sān Mèi)? If you understand, then no words are necessary; if you do not understand, then words are many. What then, is Samādhi? You know how to talk, but you do not know how not to talk. To attain to the state of Samādhi the Mind must be exactly fixed (正定 – Zhèng Dìng) upon a single point. The Mind becomes fixed on a single point of concentration, and does not move. Within Buddhism this is the great unifying practice. It is the Great Achievement of the Great Samādhi. Therefore we study Buddhism and listen to the Dharma, so that later on we can recall what we have learnt. We have to ask ourselves what it is that we have learned. We must constantly review the old so as to make it new. If we contemplate and assess our learning in this way our practice will strengthen over time. If we live a life disciplined by Dharma, then we will achieve Unified Practice Samādhi.

There is also Unified Form Samādhi (一相三昧 – Yī Xiāng Sān Mèi), what is this Unified Form Samādhi? The Sixth Patriarch said: “Non-abiding in all worldly situations means that there is no hatred and affection, because there is no accepting or rejecting. In the state of non-abiding, such situations as gain and lose, and all other dualism, become quiet, calm and peaceful as all things merge with the tranquil and desireless void. This state is called Unified Form Samādhi. In the world where everything is perceived as form, ordinary beings, as individuals, experience harm and discriminate between right and wrong and gain and loss. This is all part of living in the world of attachment to form. This attachment and clinging to form is a hindrance to the development of wisdom that overcomes all barriers. How should this wisdom be developed? It is necessary to want to eradicate attachment to the barrier of dualistic thinking. When this is successful then cognitive ability naturally manifests. This is the ability to see and understand clearly; this is wisdom. Therefore, this wisdom transcends all barriers through the realization of emptiness. Barriers of attachment are empty; people are empty, Dharma is empty, and people are empty of a sense of “self”. The practice of Dharma eradicates ego and cleanses the Mind. This is the breaking of attachment and grasping that leads to a continuous, unbroken wisdom. This continuous, seamless wisdom is the entry requirement for the attainment of the state of birthless Nirvāṇa (涅槃 – Nièpán), and the realization of the Great Knowledge and Wisdom (大智慧– Dà Zhí Huì). This cannot be compared with worldly knowing. With regard to Chán practice, the Sixth Patriarch taught that these two kinds of Samādhi should be cultivated.

What is the purpose of cultivating these two kinds of Samādhi? The primary purpose is that through the fixing of the Mind on a single point of concentration, the Mind becomes both calm and stable. The Chán tradition is a Dharma-door that develops a unified and peaceful mind. The Unified Form Samādhi and the Unified Practice Samādhi have the purpose of creating a peaceful mind. There is a work by the Fourth Patriarch of Chán Buddhism entitled “Attaining Enlightened Peace of Mind Essential Skillful Means Dharma-door” (入道安心要方便法门 – Rù Dào Ān Xīn Yāo Fāng Bián FǎMén), which also advocates the development of a Unified Practice Samādhi, and a Unified Form Samādhi. The Fourth Patriarch viewed Unified Practice Samādhi as the method for attaining a peaceful Mind, and Unified Form Samādhi as the dwelling place of the peaceful Mind. Through the cultivation of Unified Practice Samādhi the Mind is settled and becomes calm; but where does a peaceful Mind abide? It abides secure in Unified Form. Why is this the case? This is because the Mind dwells untroubled within Unified Form as all attachments to the world have been thoroughly smashed and the true principle of the Mind revealed.

As long as the Mind is divided, that is abiding in duality, then the Mind cannot be settled. It is only when the Mind is undivided, that is free of duality that it can settle. In this state the Mind does not have any notions of a personal “I”, or distinguishes between right and wrong, the ordinary and the sagely, or good and evil form; in this way the Mind settles and attains peace. Therefore the Dharma-door of the Chán tradition attains a deep and peaceful Mind. The Second Chán Patriarch inherited from the First Chán Patriarch entry into the Chán state through a peaceful Mind. No-Mind (that is beyond duality) is in a state of peace. This is called a Mind that is at ease. If the Mind abides within dualistic functioning, then there is continuous opposition and no peace can be found. There should be only no-thought, no-form, and no-abiding for the Mind to be at ease and at peace. If there is separate thought, form, and abiding, the Mind will be forever divided and continuously restless. How should we practice so that we can realize Unified Form Samādhi? The Fourth Patriarch taught a technique called “Maintaining Non-movement” (守一不移 – Shǒu Yī Bù Yī); this is Unified Practice Samādhi. In cultivating Unified Practice Samādhi it does not matter what method of meditative concentration you use, providing that the Mind remains still. This does not mean that superficial practice is effective, it most certainly is not. It is no good using one method today and a different method tomorrow. Chanting Sūtras today and chanting the Buddha’s name tomorrow will not achieve Unified Practice Samādhi. Instead the Mind must be focused on a single point and must not move. The Tiāntái School (天台宗 – Tiāntái Zōng) teaches their students to attain meditative insight through stilling the Mind. The great Chán master Zhi Zhe (智者大师 – Zhì Zhě Dà Shī) says in the “Chán Wisdom Method of Release” (释禅般罗密 – Shì Chán Bān Luó Mì) that fixing the Mind on a single point of concentration prevents the Mind from scattering and is the fundamental method of Chán training. The Fourth Patriarch teaches development through maintaining non-movement. Bodhidharma teaches that we should firmly abide in non-movement of the Mind. This is the Dao (道) or “Way” of attaining the principle of Chán; it is the gateway that is secured through fixing the mind upon a single point of reference.

If a Dharma method is not deeply pursued, then the Mind cannot be adequately fixed and will not settle down. Regardless of the Dharma method applied, the study should be thorough and in depth. In depth study is necessary and this should always be kept in mind, particularly in light of the Sixth Patriarch’s teaching about maintaining a pure and continuous Mind. It is important to cultivate a straight and continuous Mind that does not bend or deviate, even for a moment. A pure and continuous Mind must be maintained always. Whether walking, standing, sitting or lying down, the four awe-inspiring practices and the cultivation of principle should be the guide. When cultivating Pure Land Buddhism, the object is exactly the same, the Mind should be disciplined so that it becomes still and confusion ceases. What is this state beyond confusion? It is Unified Practice Samādhi. Individuals may use different Dharma-door methods at different times, but the objective must be clear. Are you clear on what this objective is? The objective is to directly perceive the Buddha-nature. The teaching points directly to the essence of the Mind; perceive this nature and become a Buddha. If you look within you can perceive the nature of the Mind immediately and attain enlightenment. You can achieve the Realm of the Western Paradise (西方极乐世– Xī Fāng Jí Lè Shì) with ease. The Pure Land (净土– Jìngtǔ) will manifest in the ten directions; any one can achieve this. However, if you use dualistic thinking and perceive the West as being different from the East, then the Mind is discriminating. How can realization be attained in this dualistic state? The Sixth Patriarch taught that if the Mind does not move (i.e. does not discriminate), this is the Bodhimaṇḍala, the holy site, or the Pure Land. The fundamental method of Chán practice is the cultivation of Unified Samādhi and Unified Form Samādhi; both of which creates peace in the Mind. the early stages of training, however, require a strong and sustained effort, as the Mind still has the habit of discrimination. In this way discrimination in the Mind can be uprooted, and good karmic roots cultivated. Good actions and intentions replace bad actions and intentions; this is the power of a pure and straight Mind. In this state dualistic thinking ceases and all things become one with the Buddha-dharma, and are reflected (i.e. manifest) in the realm of the Buddha.

3) About the Style (Tradition) of Chán

This is the third talk about Chán. What is the style (or tradition) of Chán? The tradition of Chán is defined by those characteristics which are both unique and specific to the Chán School. The Chán School has its origins in the Chán principle; from which emerges the Chán practice that is the embodiment of the Chán style or tradition. This is the definition of the Chán style. Even when this is known, it is still difficult to talk about Chán. Why is this? This is because in the past, the various Patriarchs of the Chán School all taught in different and specific styles unique to their own circumstance. As a consequence, the methods (or styles) of teaching were not the same. However, a separate and distinct Chán practice was not established outside of the circumstances of everyday life, but is firmly rooted within the circumstances of everyday life. This is the basis of the Chán School adapting to circumstance, and demonstrates the practicality of the tradition. Therefore the ability to adjust to everyday circumstance is the foremost characteristic of the Chán tradition. The original Buddhist teachings in general adapted to everyday circumstances and because of this many different Schools developed. If this adaptability was not present, then in certain circumstances we could practice Dharma and in other circumstances we could not. In reality the purpose of life lies in its transformation. This is why Chán is a very popular form of Buddhism with an appeal that reaches both high officials and ordinary people. All can study Chán; all can enter Chán and all can realize enlightenment through the Chán method. This fact demonstrates the adaptable equality of the Chán practice, and is evident in the transmission of the lamp records such as the “Finger pointing at the Moon Record” (指月录 – Zhǐ Yuè Lù), and the “Five Lamps Meeting at the Source” (五灯会元 – WǔDēng Huì Yuán), where Chán masters instruct people from all walks of life. From the king and high officials, down to the ordinary people in the street, the Chán masters accepted and instructed them all, and in so doing facilitated entry into the Chán tradition and the attainment of enlightenment through its method. Therefore, the second aspect of the style of Chán Buddhism is its popularity. The Chán style is both active, and at ease; it does not contend and remains detached from the outside world. In this way the Chán practice fully adapts to the different circumstances applicable to the common people, and in so doing facilitates the transcendence of duality.

When we read the collected sayings of the Patriarchs, we see in the ancient times the style of behavior and practice of Chán Buddhist Masters. It is clear that they are not sitting in meditation on a daily basis, so what are they doing? How and where are they practicing the path to enlightenment? They light a fire and they cook food, plunging in they select vegetables. Wandering on foot, it is within these specifics of everyday life that questions are answered through the use of Chán allegory. The venerable old monk Zhao Zhou (赵州老和尚 – Zhàozhōu Lǎo Hé Shàng) was 80 years old he was still wandering on foot from place to place, he said, “If I am bettered by a 3 year old child, I learn from him; if I am better than an 80 year old man, I instruct him.” In this manner, and through this style of activity, he was able to travel through society unhindered. He moved around on foot and did not live out his days in a temple. Instead he preferred a carefree life with no attachment, adjusting himself to circumstance along the river banks or in the forests. Everywhere, including the mountains and rivers, was transformed into a Bodhimaṇḍala, or “Holy Site”. These characteristics of Chán have ensured its place amongst the everyday lives of the common people. This demonstrates its adaptability; as there is nowhere that it does not function. Chán is popular amongst the people because all can study it exactly where they happen to be. Chán has been compatible with everyday life in the past, and remains compatible today. The Chán style transcends all social barriers and has an equal appeal amongst the ordinary people, as it does amongst those in high government office – it rejects neither. For instance, not only have I instructed ordinary people, but also those from the upper echelons of society.

During the time period between the First and Sixth Patriarchs, Chán practice was often carried out away from the scrutiny of the upper classes. Practitioners remained far away from the upper classes so that they could remain free of attachment and roam where they liked unhindered. In its initial period the Chán tradition had several generations of founders. The Fourth Patriarch was summoned three times by the Táng emperor Tai Zong (太宗 – Tài Zōng), but he refused to go. The Fifth and Sixth Patriarchs also refused to travel to the emperor and instruct him in the Dharma. They lived strictly in accordance with the Dharma and did not deviate from its position. As monks they lived happily but impoverished, following the Dao in remote areas. In this way Buddhism was preserved and strengthened and was not disrupted by upheaval and social change occurring in the world. The popularity and adaptability of the Chán method has been of great importance for the development of Buddhism in China. Even Chairman Mao has said: “The Altar Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch is the Buddhist scripture for the Working Class.” We certainly can see that kind of spirit emanating from the Sixth Patriarch’s Altar Sūtra, and I feel that it is a very important and popular Dharma – a Dharma for daily living. From the ancient times until now, many people have studied this Sūtra and followed it to the letter. Many have attained endless benefit from this study. This serves to demonstrate the adaptability and popularity of the Chán method, and how this has generally assisted the Buddhist cause in China. I think that it is important that we carry forward this special path of popular and adaptive Chán, so that Buddhism can remain integrated in society and live in harmony with it. This ensures that Buddhism is able to change with the times and remain relevant.